Boston Line Dancing

Sydney Woogerd

Blackout Country’s weekend country dancing competition on Nov. 8, 2025

Photo credit: Sydney Woogerd

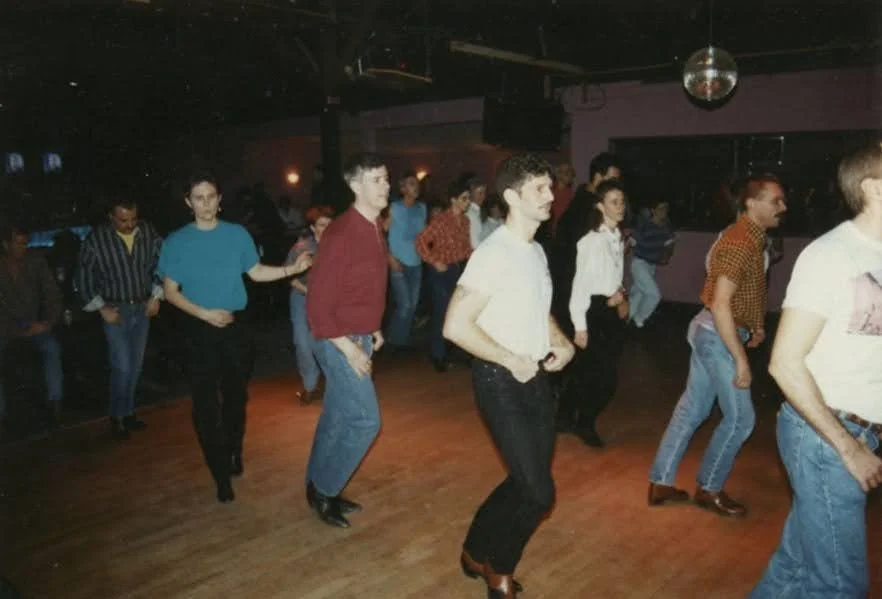

Over 100 heels stomp the ground as the words “blue jean baby” blare through the speakers overhead. A mass of bodies — some with their hats backward, holding drinks in their hands, others with paper fans and high-rise jean shorts — stand in uneven lines. They all swing their feet behind them to the lyrics of “American Kids” by Kenny Chesney before turning to their right and continuing on with the steps to the chorus.

Along the edges of the cluster, novice dancers look down at the cowboy-boot-clad feet of their neighbors, their moves delayed slightly as they try to piece together the footwork. Occasionally, they run into other dancers when a tough spin or change in direction is thrown their way.

As the dance concludes with a final four claps, the group disperses, whooping and cheering from the center of the room. Almost immediately, the intro of "Phat” by DaBaby starts up. New dancers — almost all of them in their 20s — run across the wood floor, bouncing to the bass of the rap song, shaking the ground beneath their feet. Red and white bandanas tied to blue jean belt loops sway with the hips of their owners as the group turns round and round to the beat of songs by Pitbull, T-Pain and Kesha.

“There's a lot more non-country (songs),” Julie Kaufmann, who has been line dancing in Boston since 1991, said. “Used to be it was country western line dancing. And then every once in a while, some other song would come in. Now more [songs] are non-country than are country.”

New dancers — as young as 18 — are coming to Ned Devine's, a bar in Downtown Boston’s Faneuil Hall, which hosts line dancing nights twice a week. In a city where 40% of the population is between 15 and 34-years-old and line dance trends are gaining traction on social media nationwide, Boston’s youth line dancing scene is booming.

Viral moments like Miss Shirley’s dance to “Boots on the Ground” by 803Fresh on the Jennifer Hutson Show, and new line dances to songs by Shaboozey, Ed Sheeran and Beyoncé have garnered millions of views. As a result, line dancing has established itself firmly in many bars in Boston.

“There's a whole cross-section of these country-sort of behaviors showing up in the city,” said Gedina Jean, a musician established in Los Angeles who recently partnered with Boston’s Line Dancing Queens to create choreography for the release of her new single “Your Beard.” “[It] attests to the widespread amalgamation of country and pop music and how it's being accepted and welcomed in.”

Lyric Jackson, the organizer of Blackout Country Dancing, and a front-runner of the Boston line dancing bar scene, said things started picking up in Boston in January 2023, as the city was fully reopening from COVID-19 and line dancing was going viral on social media.

“All of those things combined made it a great recipe for blowing up the way that it did,” Jackson said. As a member of the Coast Guard, Jackson was deployed to Hawaii right as the line dancing community was beginning to grow. “When I came back, I didn't know any of the people. A lot of the dances started looking different. I was only gone for a couple months, and it really, really did change,” she said.

In 2022, when Jackson first went to Loretta’s Last Call, a country bar in Fenway that hosts line dancing on Sundays, there were only 40-50 people there, mostly dressed in sneakers and shorts. Jason Peterson, a DJ and instructor who taught line dancing at Loretta’s every Tuesday and Sunday for nine years, said that the group grew to 200 people a night by summer of 2025, oftentimes with a long line out the door. Since then, Peterson has begun hosting his nights at Ned’s instead, a bar with a capacity of over 350, and it still gets packed.

While Ned’s might be one of the more popular joints in the city, it's by no means the only one. In the greater Boston area, there are over a dozen line dancing bar locations.

And if someone isn't looking to go out, there are thousands of videos online that give people a chance to practice at home.

Young adults with access to social media have gotten serious, practicing dances at home as well as at the bars. As the dancers get more dedicated, the dances get more extravagant and people tend to add their own spins to moves, literally.

Back at Ned’s, a man in brown cowboy boots and a button-up jumps up and down in the middle of the crowd, stomping his heels as hard as he can on the wood floor. Dancers around him hit their own heel into the ground to the first few seconds of the "Bombshel Stomp.” In the corner of the room, a girl cools her face with a fan nearly the size of her torso while she talks to Peterson behind the DJ booth.

Halfway through the song, the dancers scream “the barn is on fire” and begin running across the floor in all directions, dipping and dodging each other before finding another spot in line and hitting their heels on the floor again.

On the cobblestones of the road outside Faneuil Hall, the pulsing beat of Ned’s line dancing songs echo across the street while passersby look up toward the open windows, perplexed as they walk. They look at each other with confused looks, as the sound of clapping and cheering comes from the 280-year-old building, accompanied with neon green, red and blue strobe lights.

While the community continues to grow in Boston, line dancing is still a relatively unexpected hobby in the city.

“Not a lot of people know that we're here and we do this,” Megan Mahoney, Blackout Country’s social media organizer, said.

And few know how long line dancing has been a part of the Boston community, even among many of the dancers today.

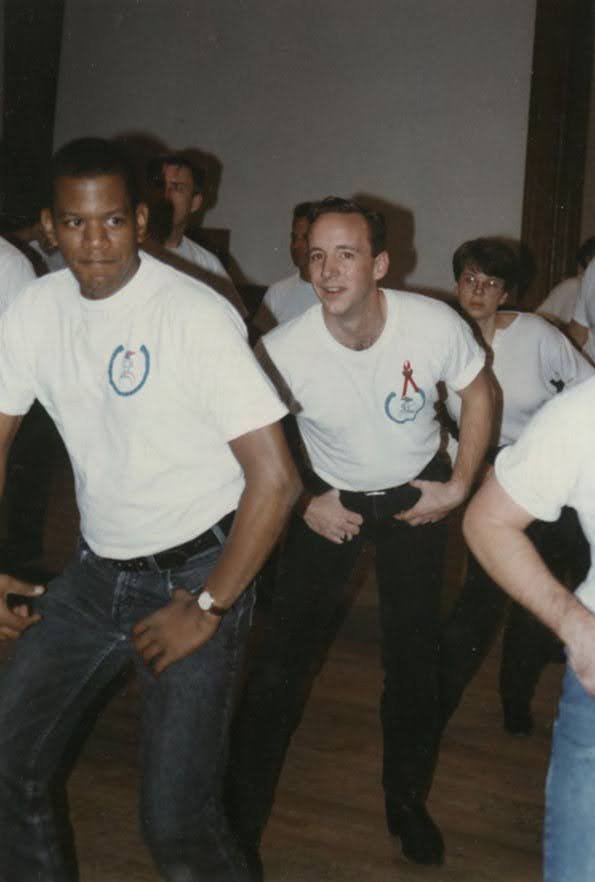

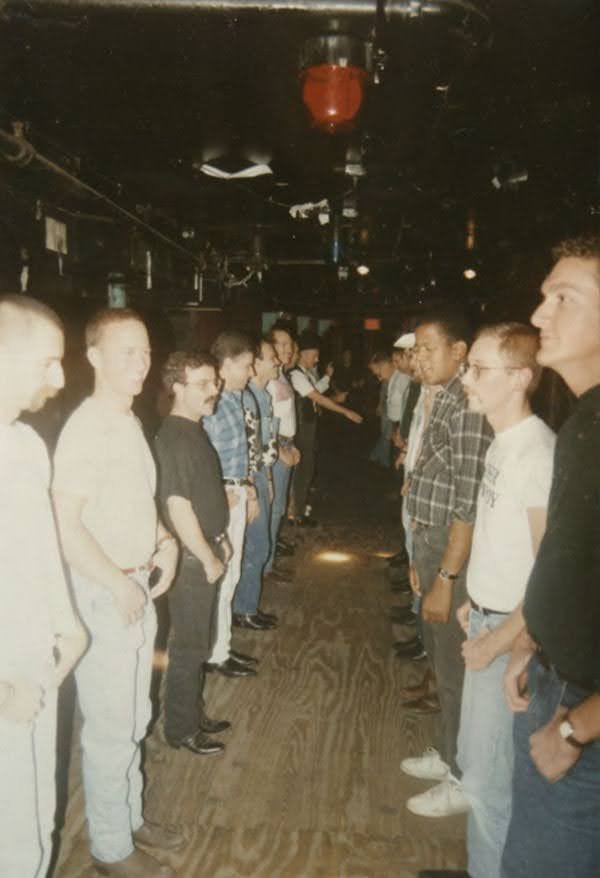

In 1985, a 37-year-old Kaufmann walked into a country western bar for the first time while visiting San Francisco from Boston. At the same time, on the same dance floor, line dancing, two-step and swing ran simultaneously in front of her. Though she already had experience with swing dancing, Kaufmann had not yet been exposed to the line dancing world, and, back then in Boston, there wasn't much of a community yet.

Once home, Kaufmann explored the now closed Peabody bar OK Corral, which hosted social line dancing. She began going weekly. She recalls while working for the Boston AIDS Action Committee in 1991 that she had multiple people from out of state ask where they could try dancing in the city.

“Country western dancing, both line dancing and partner dancing, was very popular in the LGBTQ community, but there wasn't anything in Boston,” Kaufmann said. “So some of the people said, ‘Well, can you run a dance?’”

Knowing two line dances fully and having only a few years of experience in the community, Kaufmann started hosting increasingly popular gatherings for those with HIV.

Then, in 1992 “Achy Breaky Heart” by Billy Ray Cyrus hit the scene and skyrocketed the popularity of line dancing nation-wide.

“That all of a sudden thrust it into [everyone saying] ‘Oh, wow, that looks like fun.’” Kaufmann said. “[It] went viral, before there was the internet.”

As a result, bars and nightclubs started hosting weekly and monthly line dancing nights all over the city.

Right around the same time, an organization called Gays for Patsy (GFP) reached out to Kaufmann, asking if anyone in her line dancing circle would want to join them to march and dance in the Boston pride parade.

From then on, line dancing only grew in popularity, especially among the gay community.

“There was a time when we had dancing seven nights a week,” Art Sullivan, a line dancer who joined GFP in 1992, said. “It was very popular when I first started, and we had numbers up into the hundreds coming to the dances every week.”

Photo courtesy: Queer History Project, accessed at the University Archives and Special Collections, University of Massachusetts Boston.

The Boston line dancing scene slowly adopted new dances as people in the community ventured out to other major U.S. cities and brought back new styles.

“They come back with the line dance and say, ‘Oh, I learned this dance.’ And they taught us what they thought it was,” Kaufmann said. “Sometimes it was right, and sometimes it was slightly varied.”

Boston began growing its own eclectic line dancing culture, fused together by interested locals and transplants from other states. It continued like this for nearly a decade before the turn of the century. In the early 2000s, things changed.

“It kind of waned off. The crowds were much less, the dancing venues vanished,” Sullivan said. “Everything ebbs and flows, you know, the biorhythms. It's up, it's down, it's up, it's down. It had its moment, and then it was in decline.”

Part of it can be attributed to the flow of business, Kaufmann notes. Oftentimes, when people are serious about dancing, they won't drink, which makes things tricky for nightclubs and bars trying to make money.

“Bars are not in the business of making dancers happy. They're in the business of selling food and drinks,” Kaufmann said. “If offering people to dance is going to bring people in to buy drinks, then they'll do that. And if that doesn't work, they'll try something else.”

In 2010, Peterson, who was born and raised in Massachusetts but had never been line dancing before, went to a bar called Charley Horse in Bridgewater for the first time. Over the course of the next three years, he continued to go weekly until, one day, he was asked by the establishment to start teaching lessons and growing outreach.

“Sign me up. I'll do it,” he said. “But, teaching on that night once a week turned into a couple of other bars, saying, ‘Hey, can we do a line dance night?’”

He started teaching more nights at different locations. In 2014, Loretta’s Last Call opened right across the street from Fenway Park and started hosting line dancing nights and lessons. Peterson spent a few years dancing socially there before taking over lessons in 2016. At the time, they had around 30 regulars, but the demand was high enough to start doing two nights a week instead of one. Slowly, the community began to grow again, and Peterson continued to book gigs.

Then, in March 2020, COVID-19 spiked and a state of emergency was declared. With quarantine and restrictions across the city, it simply wasn't possible to hold line dancing nights with dozens of people in a single large room. Like everything else, line dancing was put on pause.

But once restrictions were lifted slightly, line dancing seemed to be the way to go. While other country dancing styles like swing and two-step were no longer allowed because of physical closeness, the principle of line dancing was slightly different.

“You couldn't really go to these places with 200 people and partner dance,” Roger Orcutt, a swing and line dancer who has been in the scene for 15 years, said. “However, line dancing was completely acceptable, because you can form your own bubble around yourself. It's less contact.”

So, the line dancing scene started rebuilding its community yet again, and by January 2023, once Boston had nearly returned to pre-pandemic ways of life, the line dancing world exploded with the help of social media.

“[It] has just made line dancers crazier, in the sense of [people are] more dedicated, putting in way more time, very serious,” Vicky Falso, a co-founder of the Line Dancing Queens, said. “People are seeing it online, and they're like, ‘Wait, I need to go to this. This is awesome.’”

Even people in their teens have gotten hooked. But Megan Lee, a now 21-year-old student at Northeastern University who moved to Boston in September 2023, realized that it's hard to go line dancing at a bar when you're under 21. Back in Orange County, Calif., where Lee was raised, anyone could dance at nearly any age depending on the night. But in Boston, finding an establishment that allowed anyone under legal drinking age was nearly impossible.

While simultaneously trying to create a Northeastern line dancing club, Lee repeatedly reached out to bars hoping to establish 18+ line dancing somewhere in the city, but her attempts went mostly unanswered. One evening at a one-off 18+ night hosted by Peterson, Lee explained her reasoning for wanting more options: She didn't want to drink, she just wanted to dance.

Peterson communicated her interest with Nash Bar, another establishment where he hosted dance nights. At first, they only did once a month, 18+ nights with a small group, but in October 2024, due to high demand, the nights expanded to once a week. By 2025, over half of Nash’s line dancing population on a given night was under 21.

“It went from being tiny to like, ‘We are outgrowing this space so badly,’ and like, ‘It's so hot in here.’ We're dancing in the hallway side area, because it's so many people now,” Lee said. “It's grown to be such a big community of people that are able to come to 18+.”

In May 2025, Nash Bar permanently closed, and Peterson moved to hosting at The Harp and Ned Devine’s three times a week.

“When I started, it was mostly guys and gals in their 30s and 40s. Okay, now I'm in my 60s, and I look out at the crowd, and it's mostly people in their 20s and maybe a few in their 30s,” Sullivan said. “It's a much younger crowd. The older crowd, speaking for myself, it's tough to keep up with the energy.”

Grace Manozzi, the marketing manager for The Briar Group, which owns both Ned’s and The Harp, says that the energy is just as important as making money, even if people might not be buying as much food and drinks on dance nights.

“It's been great for the business, but I wouldn't equate that to profitability,” Manozzi said. “I haven't been in a restaurant that felt as fun and positive as it does when line dancing is going on, so I think that that's another big part of it that doesn't fall into a category of profitability. It falls into a category of atmosphere… It keeps people there longer because people are dancing and smiling and having a great time.”

And it attracts more customers in general. As the line dancing world in Boston continues to grow, attracting new members every week, most people don't see it slowing down anytime soon, but others have slightly varied opinions.

“I think that people really like having an activity. I think that people really like having a community,” Manozzi said. “I think that we're finally in a place where we were pre-pandemic. I think people are just going to really latch on.”

Others believe line dancing will peak and fade like it has in the past, with short bursts of life between plateaus of lower popularity.

“I think it's going to keep growing until something happens,” Orcutt said. “It's very cyclical. It's based off of the venues. If a venue closes, people need to go other places. Maybe they have to travel a little further, they won't go as much.”

But as long as line dancing exists in Boston, it will continue to adapt to its audience, possibly shifting farther and farther from its original country roots.

As a leader of the community and a person who grew up line dancing in school and at venues in her rural hometown of Apopka, Fla, Jackson believes we will continue to see a cultural shift away from the “country” elements of line dancing. She thinks the shift will be more significant than just the music, especially given the tension between rural, often republican areas and urban liberal climates like Boston.

“What I see happening is [the community] removing the label of ‘country’ from line dancing. It's still culturally acceptable to do when it's no longer cool to be a cowboy,” Jackson said.

In many places, it's already begun. In Jackson’s hometown, the culture is also changing. At the country bars she grew up going to, now, they only play hip-hop music.

“It’s not the same anymore. They had a giant mural that said, ‘Country music lives here.’ And now it just says, ‘Entertainment lives here,’” Jackson said. “Even country places are removing the label of country to make it more welcoming, but in doing so, they're gentrifying the space.”

Jackson knows Boston has never been rural, and the culture is different, but she wishes people knew more about what they were going out every week to do.

“If you grow up in a city bubble and you've never gone down south, I really can't blame you,” Jackson said. “[But] if you go to a country night or a line dance night and it's all Pitbull all night, all pop music, then I'm like, ‘Is it really country?’”

When it comes down to it, though, Jackson loves the Boston community, and she doesn't think she needs to police authenticity.

“That's not my battle. I just like dancing, I like having a good time, and I like creating a place for other people to have a good time,” Jackson said.

The community is really where Boston’s line dancing scene thrives. Despite how the demographics, music, culture and popularity have shifted over the years in the city and across the country, people come back again and again for the delight it brings both physically and socially.

“It’s the community. It's having that place to go that isn't home and isn't work. I get to socialize with friends. I get to look out and see a bunch of people having a great time,” Peterson said. “For me, it keeps me young, it keeps me happy. I think it's one of the best social experiences in Boston.”